I’ve decided to try to learn some of the basics of the Japanese language. At first I thought I’d limit myself to memorizing some spoken phrases only but I found myself increasingly curious with how the Japanese writing system works. I installed the Japanese keyboard on my tablet and… was immediately overwhelmed. “How could anyone make sense of this?” I thought. Rather than leave that as an open question however, I decided to answer it. I put the results of my research into a bite sized digestible blog post. This is not designed to teach Japanese (because lord knows I’m the least qualified person in the world to do so) but rather describes how to simply write Japanese on a computer and in doing so demonstrates how incredibly complex the entire process is. I have a whole new respect for the Japanese people for being able to make this language work.

If you’ve ever been curious how basic Japanese comes together into a coherent form but didn’t ever care enough to actually investigate yourself, this blog post is for you.

This HOWTO will describe what I have determined to be the requisite knowledge required to write Japanese on Windows Desktop Computer. In this example we will be using Windows 8.1.

-

First, Install the Japanese “Input Method Editor” (more commonly known as an IME)

- Go to Start / Control Panel / Language

- Choose Add a Language

- Select Japanese and press OK.

- Go to Start / Control Panel / Language

- You will now have the IME appear in the bottom right corner of your screen

-

By default, it will show up with an English “A” to indicate that you are typing with the English

- Click on the “A” once and it will change to the character あwhich also sounds like “ah” in Japanese

-

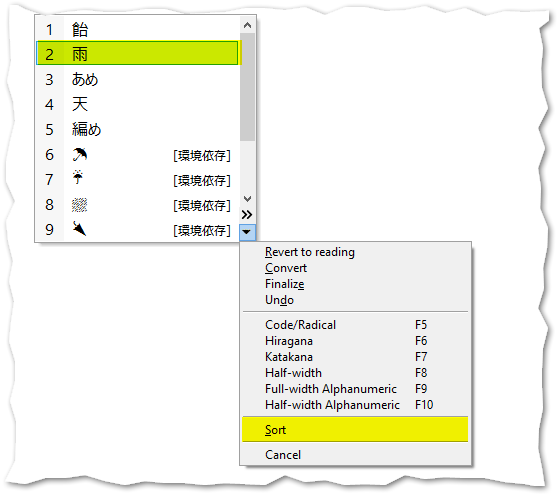

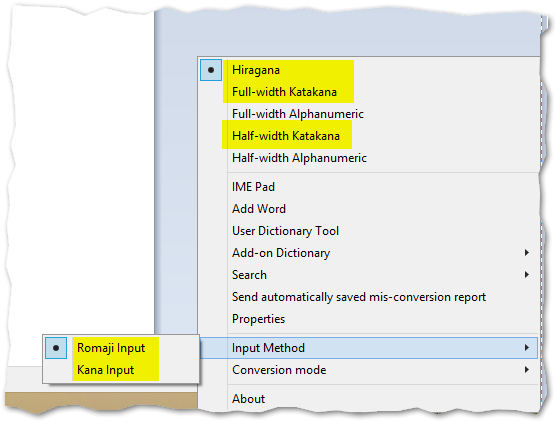

Right click on this system tray icon and you will be presented with a menu

Let’s discuss what the highlighted menu options are as they appear to be foundationally critical for any writer of Japanese to understand.

The first thing to understand about the Japanese writing system is that unlike English where we have just 26 discrete unique characters to work with, Japanese has far, far more. If you are looking for analogies, a concept similar to the English alphabet does in fact exist and is called the Kana. However, unlike the alphabet, there are actually two types of Kana – Hiragana and Kanakana. Each one of these alphabets are completely distinct and contain 46 characters each. From what I understand, Hiraghana is used primarily for native Japanese words while Kanakana is used all but exclusively for foreign or imported words. This means that both character sets are used extensively in all aspects of writing. It is not possible to learn one and not the other.

Now for the purposes of writing these languages on a computer, I’ve noticed something very interesting. It appears that each character in one kana maps 1-to-1 with a character in the other. In fact, it appears they even have the same pronunciation. But more on this later.

Next we have the half-width Katakana. It turns out this is a holdover from the early days of computing when thanks to being developed largely in English speaking or at least Romanized speaking countries, software was only designed to accommodate English character sets. Half-width Katakana is a kind of stop-gap solution to this problem where they change the encoding and visual look of the characters to fit inside an English speaking character set. From the reading I’ve done, it’s not nearly as common as it used to be but Japanese people need to know this too because it’s still used in places like cash registers and movie subtitles or other areas where space is at a premium.

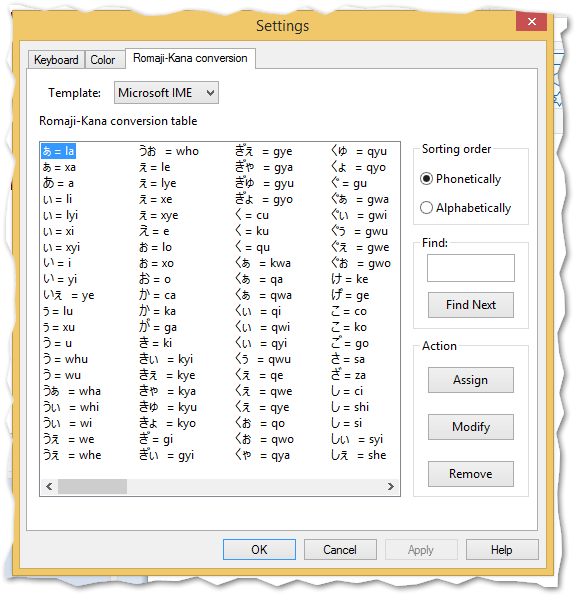

Next we have the input type which includes Romaji and Kana. It turns out that Japanese writers can input their text using either the Romanized (aka English) letters or the Kana characters. Why would Japanese people need to use English letters to write Japanese you might ask? From what I can tell it’s all once again thanks to computers where keyboard QWERTY layouts became a global standard. Even more so was the advent of the cellphone where Japanese people had to write text on a device where English was the first class citizen. So to give you an idea, I found this screenshot below buried in the hilariously complex and configurable options of the Japanese IME. As you can see, if you type “ka” for example with the Japanese IME enabled, it can instantly be converted to か.

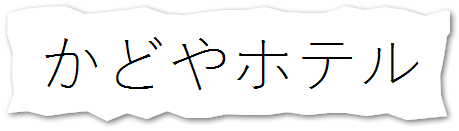

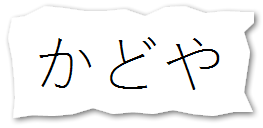

Ok so armed with this information, let’s try to complete our objective of writing the name of the first hotel I will be staying at in Japan. The name of the hotel in English is the “Kadoya Hotel”. In Japanese its:

So, how do we write that on our computer? The first thing we have to do is identify which words are native Japanese words and which words are foreign words so we know if we need to use Hirakana or Katakana.

“Kadoya” is a Japanese word so for that we will use Hirakana.

“Hotel” is a foreign word so we will use Katakana.

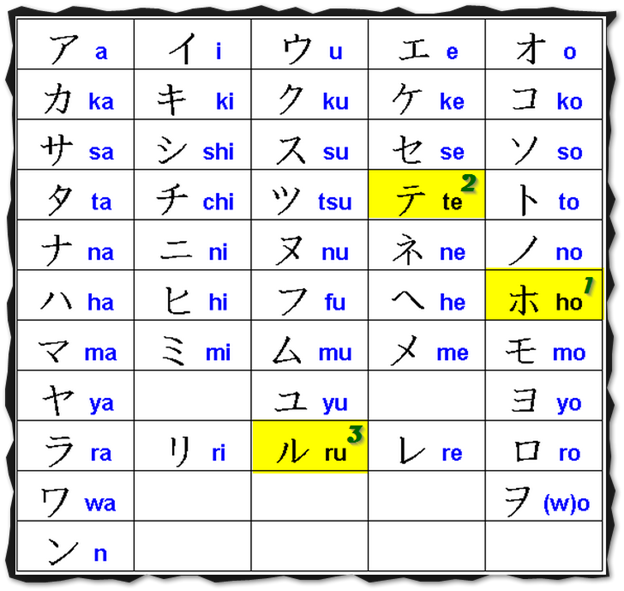

The good news is that for this case specifically, we can basically sound it out phonetically. Kadoya is 3 syllables in English. “Ka”, “do”, and “ya”. So all we need to do is match those up. We’ll use the chart below:

HIRAGANA SCRIPT

If you’re paying attention, you’ll note that #2 says it sounds like “to” but we want “do”. It turns out there is an accent character you need to add on to make it sound like this. That looks like:

Ok, so now that we’ve written the Japanese word, we now have to switch to Katakana to write the word Hotel:

KATAKANA SCRIPT

Ok, so now that we have our characters, how do we enter them into the computer? We have two options that I know of: Kana input and Romaji input. I haven’t figured out the Kana input yet so we’re going to go with Romaji.

That is to say, we’re going to type the English characters above that represent the Japanese symbols above. Let’s begin:

First, let’s type Kadoya:

- When we press “K”, the English K is inserted

- If we press “a” next, it knows this corresponds to a Japanese character so it automatically converts to that

- Next if we type “do” we get the second character we need

- Finally if we type “ya” we get the third character

Ok, cool so far. But what about the word hotel. That is a tad more complicated.

-

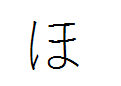

As we can see above, we should be able to type “ho” and get the character that looks like the letter “t” is crying. But if we do that we get:

Hmm, that’s not right at all. But! Have a look at the hiragana script chart above under “ho”. It’s that same character! As I said, they appear to match up 1-1. So I think this means the spoken language is the same in both cases, but the written requires distinction.

So how do we switch to Katakana? Once you have typed “ho” and the Hiraghana has appeared, press the space bar. As Japanese doesn’t formally use any spaces in its language, this key appears to be repurposed to switch back and forth between the two script types.

If we press space, what do we get?

Yep, the character we wanted. Now, whatever you do, do not press spacebar a second time. Why? If you thought what we covered so far was complicated, we haven’t even scratched the surface yet! You see, in addition to hiragana and katakana, Japanese has a third writing system.

This is the one they are most famous for and the one that drives fear into the hearts of Japanese language learners.

Kanji.

Kanji isn’t just 26 characters or 46 characters or 46 characters times two. Of course not as that would be too simple. It is estimated that there are 50,000 unique Kanji characters! Now, the good news is, the vast majority of those are very seldom used. In fact, the Japanese Ministry of Education has created an official list of Kanji characters that all Japanese people must know. They trimmed that list down to just

1,945 discrete kanji characters.

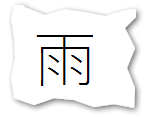

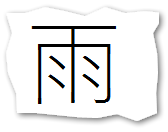

These are the more pictograph type characters that in many cases convey considerable meaning in a single character. I was playing around and I identified a simple Kanji character I used for testing purposes and that is the Kanji for the English word Rain. So what does that look like?

It’s funny to me because I immediately identified this symbol as looking out a window and seeing rain outside. I don’t know if that’s intentional or not.

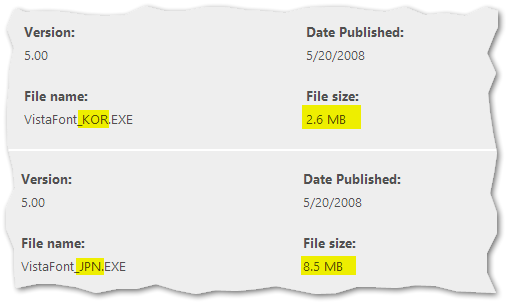

So the question is now, how the heck to I write this character on my keyboard? Especially when we already saw the full character sets above for the two other character sets. At first I thought it was like Korean where you’d assemble this final shape from a bunch of base characters. But due to the complexity of many Kanji as well as due to their sheer volume, that’s not possible. In fact to drive that point home, I just tried a quick experiment. Windows XP did not natively include support for Japanese or Korean and so those fonts had to be installed separately. I went to go look at the relative sizes of each download:

The Japanese font is literally over three times larger than the Korean font. That’s a lot of Kanji!

So from what I can tell Microsoft includes all 1,945 official Kanji characters in their IME and you can simply select from them. How do you do that? Well you need some way of filtering the list and that way that appears to be done is by:

The above picture shows the Japanese Kanji for Rain as well as it’s “on-reading” and “kun-reading”. What are these? Well apparently the Japanese people didn’t think their language was hard enough yet so they decided to introduce yet another system.

See Kanji was originally imported from China back in the 5th century which means that most of the Kanji has a Chinese origin. This means it also has a Chinese pronunciation.

But the Japanese are also a very proud people so they over time came up with their own pronunciations for the Kanji as well.

So On-reading is the Chinese pronunciation while Kun-reading is the Japanese pronunciation. So how do you know when to use which? You don’t. While there are some lose rules, it basically can only be learned through brute force memorization.

I now understand why Asian education pushes memorization so much more than Western systems. It’s out of necessity! Now the good news here is that in many ways, Kanji can be thought of more as vocabulary than an alphabet.

If English has almost 2,000 letters in it, it’d be nearly unlearnable. But English does have well over 2,000 words and that’s completely fine. So I suppose it’s not all doom and gloom.

But anyway, back to how can we write the Kanji word for rain on our computer.

You’ll note that there is a Radical mentioned and that Radical in this case is “ame”. Now what I do know is that when you pronounce the kanji for rain, it comes out as “ame” so the radical appears to be the phonetic representation of the word. So to enter it onto the computer we would:

- Type ame

- This gives us the Hiraghana of “a” and (for some reason) “nu”

- Now if we press the space bar

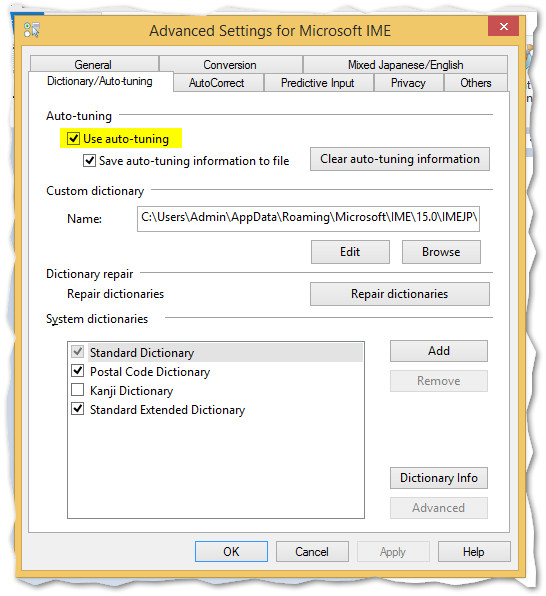

- Here we are given a popup where we can select the Kanji we are interested in. Now the crazy thing to me is, this list is sorted based on what you use most frequently (like an auto complete)

- Below I have yet another option from the Microsoft IME where you can turn this feature on and off

At any rate, after we type “ame” and pressed space bar and selected the Kanji we wanted, we get:

Summary

Ok, so let’s re-cap, shall we? Based on the research I’ve done so far, it seems that all Japanese speakers must memorize and understand the following systems to be able to write in Japanese:

| 1) | Hiragana | The base alphabet for Japanese words |

| 2) | Katakana (Full Width) | The base alphabet for foreign words |

| 3) | Hiragana -> Katakana Matching | Because the two alphabets match one to one but because only one is used for computer input, you must memorize which symbol from one corresponds to the other |

| 4) | Kanji | The 1,945+ special symbols that kind of equate to a vocabulary but is in addition to the vocabulary spelled through combinations of Hiragana and Katakana |

| 5) | Hiragana -> Kanji matching | In order to type out Kanji, you must memorize the Romaji radicals that are used to search for and select the desired Kanji |

| 6) | Romaji | (aka the English Alphabet) – Because so many phones and computers make heavy use of the Roman alphabet, you need to understand it as well to type in Japanese at all |

| 7) | Katakana (Half-width) | As Half-width Katakana is still used, you also need to be able to identify and read shapes that are proportioned differently than their full sized counterparts |

| 8) | On-reading | The Chinese pronunciation of 1,945+ Kanji words |

| 9) | Kum-reading | The Japanese pronunciation of 1,945+ Kanji words |

| 10) | Identify word origin | You need to know if a word is natively Japanese or Foreign so you know if you should write it in Hiragana or Katakana |

| 11) | Read sideways | I didn’t mention this above, but it is common for Japanese to be written on its side relative to the symbols above. So they need to be able to quickly read that too |

This is not for some advanced Masters in the language. This is just to function in society! At least for me personally, after doing this research I’m no longer as intimidated by the language.

But I really don’t think I’m going to be fluent after only a few weeks now. J

I hope you enjoyed this brief HOWTO on how to type in Japanese!

2 comments

how to type japanese in romaji with a small line on top of letter,

for example for longer o they put (-) on top of o ? thank you for

your help in advance, Nancy

I’m afraid I’m not Japanese and everything I know is in the original blog post. Sorry I couldn’t be of more help.